6 min read

6 min readSharding Using Postgres Logical Replication

Introduction

I recently wrapped up a project I’d been working on for a while: Cascade, a Change Data Capture (CDC) tool for Postgres. It streams DML changes to Kafka and routes them to different SQL databases. While the architecture is designed for sharding, my current implementation functions as a decoupled read-replica system.

While the code itself is mostly straightforward, building it pushed me to learn a lot about Postgres internals and how systems maintain availability. That ended up being the most rewarding part of the project.

In this post, we’ll look at how Postgres enables CDC under the hood and walk through the core ideas behind building a system like Cascade.

Hold on... what's a Change Data Capture?

Before we start, we have to know what we're building! So what is Change Data Capture (CDC)?

CDC is a system responsible for listening to database changes. Specifically, DML queries like these:

INSERT INTO EXAMPLE VALUES(10);

UPDATE EXAMPLE SET X = 50 WHERE X = 10;

DELETE FROM EXAMPLE WHERE X = 50;

A CDC pipeline captures these modifications, tracking exactly what changed, where it happened, and the resulting state of the data. Use cases range from audit logging to data visualizers, in our case, replicating data to other databases.

But how does one capture these changes?

Write-Ahead Logging (WAL)

How does a database (or a system in general) maintain consistency and achieve durability? Through a mechanism called Write-Ahead Logging (WAL).

The basis of WAL is that any operation is logged to a persistent WAL file before it is applied to the main data files. In the case of a crash, the system can replay the WAL to restore the state. Postgres first saves operations into a memory buffer called the WAL buffer before flushing them to the WAL segment on disk. Only then is the operation considered "committed."

WAL records are stored in a binary format.

There are two primary ways to make use of WAL for replication:

Physical Replication

Physical replication is the native way for Postgres to stream changes to another Postgres instance. It works by streaming the binary WAL segments directly to a follower instance. It is implicit, automatic, and exact, creating a byte-for-byte copy of the primary.

Logical Replication

Logical replication streams changes at the logical level (e.g., "Row inserted into Table A"). It uses a WAL Sender process and a Replication Slot. This gives us fine-grained control; instead of replicating the entire database instance, we can replicate specific tables or databases. Crucially, strictly speaking, the consumer doesn't even need to be Postgres.

To enable this, we configure Postgres:

# postgresql.conf

wal_level = logical # Must be set to logical

max_replication_slots = 10

max_wal_senders = 10

And create a replication slot:

SELECT * FROM pg_create_logical_replication_slot('slot_name', 'wal2json');

We use wal2json, an incredibly convenient output plugin that transforms the binary WAL records into readable JSON.

I used a library called pg-logical-replication to skip the boilerplate of setting up the protocol, buffering, and acknowledging LSNs.

Architecture

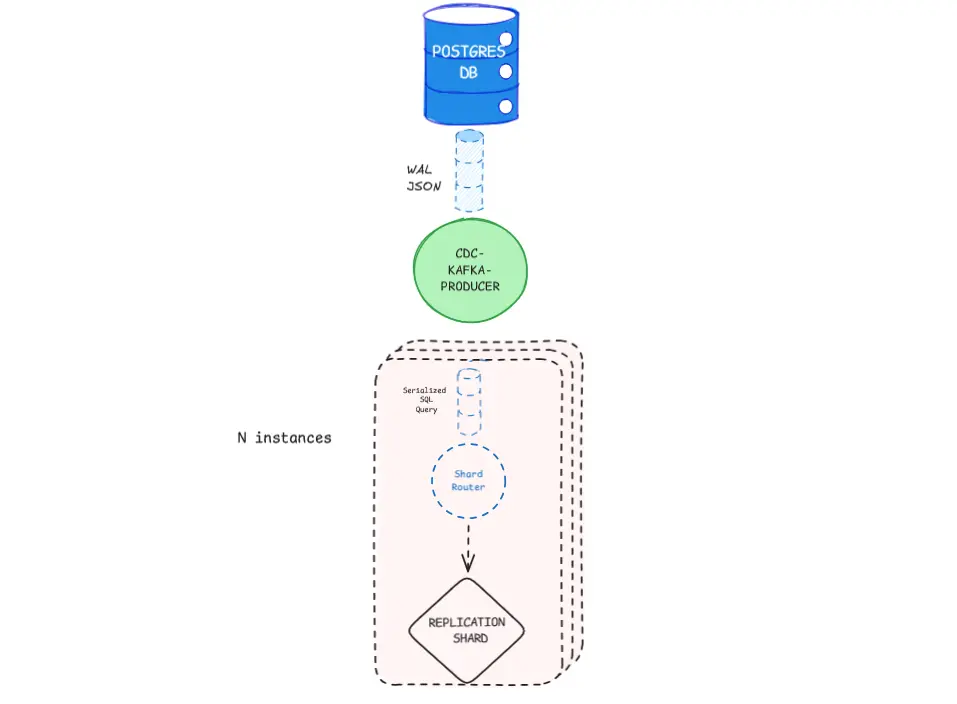

The architecture is designed to be decoupled and resilient. Here's how the data flows:

- Master Database: The main Postgres instance receives write traffic.

- CDC Capture & Serializer: The Bun service (Cascade) connects to the replication slot, receives WAL records, and immediately transforms them into valid SQL statements.

- Kafka: The serialized SQL statements are published to a Kafka topic.

- Executor (Router): Downstream consumers (shards/replicas) subscribe to the Kafka topic and apply the SQL statements to their local database.

This setup ensures that the heavy lifting of distribution and processing doesn't impact the write latency of the primary database, as the replication is purely asynchronous.

Implementation

The core of Cascade uses pg-logical-replication to listen for changes and a custom serializer to turn those changes into SQL.

Here is a simplified snippet of how the service listens for changes and publishes them:

import { LogicalReplicationService } from 'pg-logical-replication';

import { WalSQLSerializer } from "./WalSQLSerializer";

// 1. Setup the service

const service = new LogicalReplicationService({

database: 'postgres',

// ... connection config

});

// 2. Subscribe to changes

service.on('data', async (lsn, log) => {

// log.change contains the WAL data

// 3. Serialize to SQL

// We convert the raw JSON change into an INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE statement

const sqlStatements = WalSQLSerializer.transactionToSQL(log);

// 4. Publish to Kafka

// We send the actual SQL command to be executed by the consumer

await producer.send({

topic: "sql-topic",

messages: [{ value: JSON.stringify(sqlStatements) }]

});

});

By decoupling ingestion from processing via Kafka, we gain the ability to replay events. If a shard goes down, messages pile up in the Kafka topic (or the replication slot if the CDC service itself handles the buffering), and processing resumes once the system recovers.

To implement sharding, we would simply modify the publishing step. Instead of sending everything to a single topic, we would hash the primary key (or any identifier) to determine which partition or topic to send the event to.

Challenges & Learnings

Exactly Once

Now this is the hard part. Let's take this scenario: you receive the WAL log, you serialize it, and you publish it to Kafka. Your Kafka consumer receives the message, runs the SQL, but fails before committing the offset. Now since the offset is not committed, Kafka thinks you haven't processed the message, and it will retry. This is a problem because now you've received the same WAL log twice, and you've applied the same SQL twice. This could either result in a duplicate entry or a constraint violation, depending on the SQL. To solve this, we need to implement exactly once processing.

This could be patched with a Redis set to track the LSN of the last processed log; this does not solve the problem but simply shrinks the window of opportunity for the problem to occur since Redis set is much, much faster than a Kafka commit. The one true solution is to use the OutBox pattern.

Durability and the Slot

A critical lesson was managing the replication slot. If the Cascade service crashes, Postgres holds onto the WAL files because it thinks a consumer still needs them. If you don't recover quickly, your Postgres disk will fill up with WAL segments, potentially taking down the primary database! Monitoring pg_replication_slots size is mandatory in production.

Conclusion

Building Cascade was a deep dive into database internals. It showed me that you don't always need complex proprietary tools to build a robust replication system. The building blocks—WAL, logical replication, and Kafka—combined with some TypeScript glue, are powerful enough to construct highly scalable architectures.